Missouri Mountain

Three Halloweens ago, on this very day, near the ghost town of Winfield, Colorado...the mountains gave me a scare. It was not the first time, nor would it be the last.

The sun illuminated the basin below Missouri Mountain, rebounding blindingly bright off the immense canvas of white snow. It felt like nothing could go wrong; the snow was not unmanageably deep, the winds were calm, the skies were blue, and the temperature was rising into a comfortable range after a pre-dawn start. Jonathan had donned his snowshoes, but I kept my massive pair attached to my pack; I had a strong dislike for the inefficient process of putting on and walking in them.

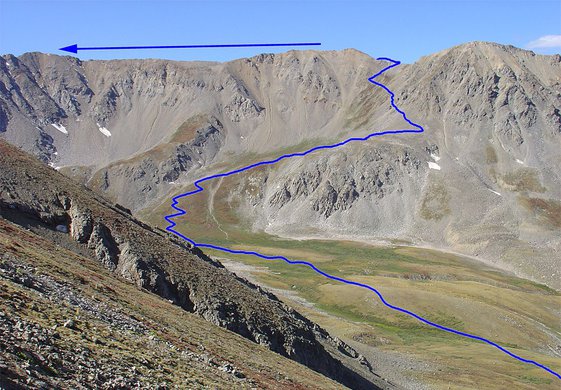

A zoom-out of our route up and across the ridge, taken in the summer, by someone other than me. (from 14ers.com)

Our task was straightforward, but difficult: we would finish walking up the gentle slope up the basin, then aggressively tackle Missouri Mountains northwest ridge, finishing with a flat ridge walk. It would have been a long day without snow, but it was Halloween, and snow had been visiting the high country for a while already. We were lucky that it was not too deep, but any amount of snow makes a hike more demanding.

I've been hiking in Colorado for three more years since this day. I like to think I am wiser. I've learned that snow travel is not always predictable. I've learned that I can't have an agenda while hiking in the snow; I can only take what it gives me. Especially in the high country, snow conditions can vary wildly over a short distance. Three years ago, these insights weren't as clear as they are today. Three years ago, I thought we would hop, skip, and jump our way across that ridge, just like I had done for a couple summers already. I even opted to wear trail runners instead of boots.

Mesh New Balance running shoes in the show

In spite of the snow, Jonathan and I made good time to the high point of the valley floor. As usual, I discovered I had forgotten a crucial piece of gear: my sunglasses. I bought those bad boys shortly after a sunny snow hike left me with sunburned eyeballs, leaving my co-workers to quietly gossip about why I had been crying, until I set the record straight. Jonathan, prepared as ever, revealed he had a spare pair in his pack. Yet again, Jonathan's over-preparedness compensated for my less-than-perfect packing. I thanked him as much as I could, and made a mental note to take better inventory when packing. Without rubbing anything in, Jonathan accepted my thanks and we turned our attention to the steep slope ahead.

We had clearly tapped into our reserves while powering up the basin. The sun beat down from its apex, with only a thin shell of atmosphere between us to lessen the intensity. Neither Jonathan nor I were strangers to that type of grind, but getting up to that ridge was still very tough. Every so often, the warming snow would collapse or slide under our feet, erasing a few footsteps' progress. Jonathan's nearly unflappable nature was no defense. He got angry. Jonathan was regularly hurling curses at the snow, which, in a twist of delicious mountain irony, neatly absorbed all the sound. Back down in Denver, we felt like rugged, capable mountain men. But up there, Missouri Mountain was busy stripping away all our ideas about ourselves.

The face of a man who is tired of falling down in the snow

After getting walloped with some of the most brutal 1300 feet of ascent I can recall, we were happy to be topping out (known colloquially as "gaining the ridge"). There were only five feet remaining. Jonathan, wearing snowshoes with sharp blades called crampons to dig into snow and ice, went first. The snow was too warm. That steep, slushy, five feet of snowy suck was torturing him. Nearly there, then the snow gave out and he slid below where I stood. A military man, never a quitter, Jonathan attacked again. And again. And again. This type of setback seemed uniquely agonizing for Jonathan. I have never seen him so angry as when he loses his footing on snow, and here we were running a clinic on it. We both gained the ridge, but getting there might be the least graceful bit of mountain movement that either of us have attempted to this day. We looked pathetic. But at least we were done with the hard part, right?

Jonathan and the wind-sculpted ridge

The following ridge walk was no cakewalk. Sure, the elevation gain was mostly finished, but my optimistic ass had failed to account for snow drifts. Wind blows snow across the ridgeline in interesting ways, taking it from here and piling it up there. We had no discernible trail to walk on, so we resorted to stepping into deep snowfields and scrambling across boulders. Standing on the spine of the mountain, we no longer enjoyed the wind protection that the basin had provided. The winter winds, a near constant in this part of the country, blasted me in the face the moment I poked my head above the ridge. There is a sense of urgency in these persistent westerly winds: they will never stop, but they still desperately need to beat you down as soon as possible. Continuing to push back against the deep snow and fierce gusts, we were hustling, feeling like the summit would pop up at any moment. But snow makes you move slowly. More slowly than our brains would allow us to comprehend. We ditched our nonessential gear, becoming nimbler for the final bit of rock-hopping and snow-swimming.

And hey, we made it. We both hooted and hollered, for the first time fully acknowledging how hard that whole ordeal had been. You can only admit that after the fact. We also shared a kind of wordless appreciation. This was our ninth big mountain together. Neither of us could explain why we continually decided to take on this type of challenge, but neither of us doubted it was worth it, either. There is something about how one reacts to summiting that reveals their deepest feelings about the whole experience. Reaching the summit and immediately sitting down with a snack? Now, that would be reasonable. But, again and again, Jonathan and I forget pictures and resting and eating at first. Our conversation sheds its torpor from the grinding hike, and it gains a frantic energy as we talk about our victory with more candor than we would have dared earlier. The air crackles with the electricity of two people who just love to be up there. Simple as that.

Always psyched. Always.

The ridge walk back would not be easy, but it would be easier than descending straight down a sheer drop to our deaths. So we headed back across the ridge. Now there was no summit pulling us forward, just a large meal many hours away. Despite the solar heat in the air, the snow on the ground had kept my feet close to freezing all day. But I was finished taking inventory of how my body was feeling; I simply wanted to be done. I was living in the state of painful numbness that comes after a herculean effort like climbing one of Colorado's high peaks. In fact, if a helicopter had appeared on the summit and offered to take us back to our car, I would have accepted. If all hikes could just go uphill and then into a portal to my home, that might be okay with me. But I suspect there is a lot of character building during the boring, painful slog down.

There are many ways to descend a mountain

We were able to cash in on a unique winter experience called glissading. Remember those horrible 1300 feet of grinding up to the ridge? Planted on our rumps, we slid down that stretch in mere minutes. It was almost enough to make me forget the cumulative pain of the day. Almost. We bottomed out in the relatively flat valley and resumed walking, but not before a wardrobe change and a bathroom break.

As is customary on long hikes, my least favorite part of the day was the last stretch, walking down to the trailhead. The stakes and excitement were low, and we were fresh off a surprisingly challenging ascent. Missouri Mountain had allowed us to pass, but we didnt have much left to offer. The air continued to warm, and my colder parts started to warm up...an uncomfortable experience in itself. My trail runners had been completely shredded by the traction devices I was wearing. I looked down at the sad state of my feet. On such a victorious day, it can feel like nothing will go wrong once the most obvious danger has passed. We had gone up to the roof of the contiguous United States and returned down to the safe valley floor. We had won, I thought.

After ten hours in the snow, my feet were having a hard time warming up. My choice to wear trail runners had been foolish. They offered little insulation and no waterproofness. Across two summers and a winter, I had been steadily gaining confidence in my abilities as a Colorado mountaineer. Missouri Mountain checked my machismo. "No boots? Really? Well, this oughta learn ya." False confidence, rooted in a state of mind rather than in preparedness and experience, is useless. I had chosen to leave my boots in the car. When my feet went numb, I wrote it off as "just something that happens". And when I had no feeling in my big toes for the following two months, I couldn't blame the mountain...all it ever did was exist. I was the one who had caused nerve damage to my own feet.

All that remained of that day on Missouri Mountain was the short trip report I scrawled on 14ers.com:

"Very hard hike w/ Jonathan. Destroyed my trail runners with microspikes. Toes hurt and we got delirious...10 hr effort"